The photos last week caught my attention. The chapel, covered in snow. The lone pilgrim, covered in a poncho but soldiering on.

I knew this place, and the people who guarded pilgrims along this stretch of road. Although when I’d passed by, the sky was grey and full of rain, not snow.

From Walking to the End of the World:

As we left Zubiri, Marieke and The Dane each split off to walk alone, but Eric and I plodded forward together through the steady drizzle. Just past Larrasoaña, we noticed a crumbling church by the road. The doors were open, so we went to check it out and see if there was a guest book to sign.

When we got to the doorway, we realized that this wasn’t an active church at all, but a restoration project in progress. The interior of the chapel was gutted, and there were huge holes in the brick floor and the plaster walls. But there were also candles lit near where the altar used to be, and I could make out the edges of a simple fresco on the wall above it.

A man emerged from the choir loft and introduced himself as Neil, from South Africa. This was his project.

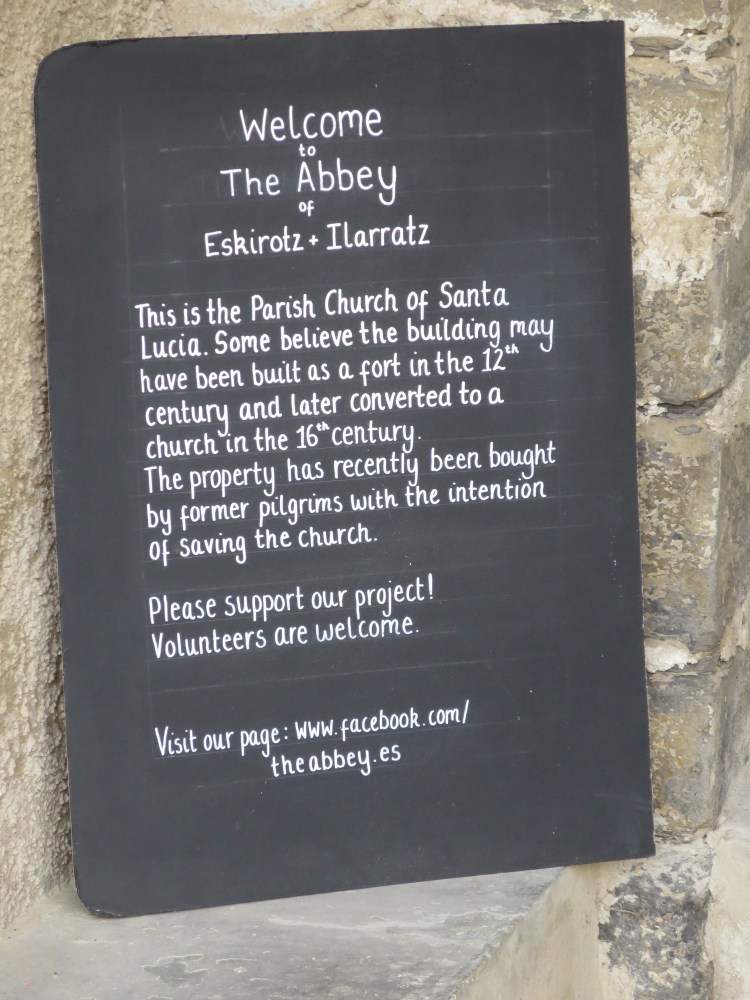

With great enthusiasm, he showed us around the abbey chapel, parts of which he said dated back to a twelfth-century fort, which was converted to a chapel for the Knights Templar. The Templars hadn’t been active since the fourteenth century, though, and the size and coffers of the Spanish church had been steadily declining for centuries. The Abbey of Eskirotz & Ilarratz had sat empty, abandoned for decades before Neil and his wife, Catherine, purchased it from the Archdiocese of Pamplona.

I stopped him. “You just bought a nine-hundred-year-old abbey? A person can do that?”

They can, he assured me, although it takes a lot of work. Spain’s bureaucracy is notoriously inefficient, but the church couldn’t sustain all of its aging buildings, and for them it was better to sell it to Neil than to leave it to rot.

“Gypsies,” Neil told us, waving at the belfry. “They come and steal everything — the wires in the walls, the bells from the belfries. I have to sleep here every night for now, to let them see that the place is inhabited again.”

Templars and gypsies, belfries and frescoes…I started to see past the modern Camino and into the corners of Spain. Eric, too, looked interested for the first time since we crossed the border.

We lingered at the abbey for an hour or so, and The Dane decided to stay and volunteer for a week. Neil and Catherine were the talk of the albergues for days. We were all intrigued by a pilgrim who stayed. This idea of living on the Camino forever was something most pilgrims dreamed about over dinner, of course. Let’s just buy one of these abandoned towns! Let’s just run an albergue! Let’s be part of this story forever!

Well, Neil and Catherine had actually done it. They were our heroes.

Since then, I’ve stayed loosely connected to Neil and The Abbey through social media and email. Their program continues to grow, with new pilgrims discovering it every day and then telling their friends.

On their Facebook page, The Abbey describes their story this way:

Our vision is to crowd-source the skills, the means and the resources needed to restore this neglected 12th century church. The church is rumoured to be a Templar church and symbols contained in and around the building seem to confirm this. Our research is ongoing but given that few records exist piecing the building’s story together is a challenge. Our vision for the church is that it will become a museum to itself. The building has lived through so much – the invasion of the Moors, The Spanish Inquisition, Napoleon’s crossing of the Pyrenees, two world wars, and the Spanish Civil War to name but a few… Our plan is to create a not for profit establishment where pilgrims can take refuge under shady oaks from the scorching summer sun. A place where they can relax in hammocks alongside the stream that flows through the garden or sleep out under the stars at night. We dream of creating a space where the commercialism of the Camino can be held at bay for a little while longer… to create a space where the true spirit of the Camino will be fostered. If you have any spare time, a particular skill set, knowledge specialisation, or any financial / material resources with which to help, we would love to hear from you. So many historical buildings on the Camino have been allowed to go to ruin – our hope is that by saving this one we’ll be able to create a ‘home from home’ for fellow pilgrims travelling on the Camino de Santiago.

For more information, check out their Facebook page. And if you want to support them, there’s a GoFundMe site.

If you’re walking the Camino Frances: The Abbey of Eskirotz & Ilarratz is situated on The Way of St. James (Camino de Santiago) shortly after Zubiri and before you reach Pamplona, in the Valley of Esteribar. The church is on the right-hand side of the road 150 meters past the village of Ilarratz on the way to Larrasoana.

(Also, if you’re independently wealthy and want to support a couple of Americans who dream about preserving parts of the Camino, my contact information is on the About page. 🙂 )