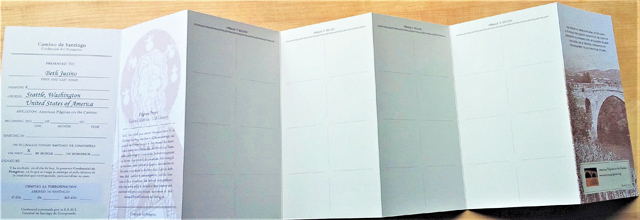

It’s here! A week ago I went to the American Pilgrims of the Camino website and requested a new credential for my upcoming mini-Camino. (I’ve started to call it Camino 1.3, because I’ll walk about a third of the Camino Frances.)

And now here it is, all crisp and blank and pretty.

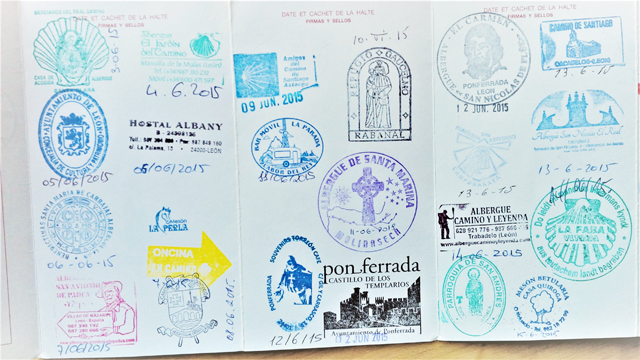

In less than three months, it will look more like this:

What is a Camino credential?

This is the “passport” of the Camino. Pilgrims along the trails (in France and all across Spain, not just on the Camino Frances) carry these. The albergues, gites, guest houses, and most hotels along the Way stamp and date your credential when you stay overnight. Many of the cathedrals, tourist sites, and quite a few bars and restaurants also have stamps to add.

The stamps become a reflection of your unique Camino experience. No two booklets end up quite the same; even Eric and I, when I compare them, have a few different stamps.

Some stamps are all business. Some are whimsical and bright. We have one hand-drawn stamp from a donativo gite in France that was run by a family. There’s a hand-colored stamp from Cahors, and the one that the gite owner in Lauzerte carved herself.

There’s no rule about who can and can’t offer a stamp. Some rest stops and pilgrim shelters along the way offered their own own stamps. And then there’s my favorite: the friendly guy at Finisterre who had designed his own stamp that he offered to anyone passing by.

The official reason for the credential is to prove that you are a pilgrim of the Way, and not just a tourist trying to get cheap lodging on a vacation. The stamps and dates show that you are steadily moving in the direction of Santiago. When you arrive in Santiago, the volunteers at the Pilgrim’s Office will use your credential (credencial in Spanish) as evidence that you have earned your Compostela, the certificate of arrival.

Note: you need to acquire two stamps per day in the last 100 kilometers – the only ones that really “count” for the Compostela – to prove that you made the journey. (However, in my experience, when you plop down two full credentials, with stamps going back more than two months, no one really examines those last five days that carefully.)

The other reason for credentials is that they make a fantastic visual record of the experience. In the evenings, Camino pilgrims often pull out their credentials as they talk with new friends about where they’ve been. You stopped in that town, too? Where did you stay? Oh look, you were in that cathedral just one day before me!

If I’m not going to Santiago, do I need a credential?

Anyone who is walking any part of the Camino benefits from a credential, no matter where you start and stop. This summer, I’m only walking as far as Burgos. But I’ll have my booklet for those ten days. Of course, I want it as a souvenir. But more important, most municipally owned hostels, and some of the church- and volunteer-run ones, require that anyone staying there have a credential.

When Eric and I walked in 2015, we had a friend who “dropped in” with us only from Leon to Astorga. She had a credential and collected stamps for the few days she was on the path. We also had a friend who came for five days and didn’t have a booklet. Those were sometimes hard days to find lodging.

Where do I get a Camino credential?

In order for a credential to be accepted in Santiago, it must be issued by a recognized association of the Camino. (This is a fairly new rule, made in response to some of the shadier Camino tourism companies trying to make their own “credentials” and selling them for as much as 25 euro. Officially recognized credentials are free, or cost no more than a euro or two.)

There are Camino societies in many countries, and most of those issue credentials to their citizens. (At the bottom of this page is a list of where to get an approved pilgrim credential.)

You can also pick up a credential in many of the bigger cities/major starting points along the Way. The cathedral of Le Puy and the Pilgrim’s office in St. Jean Pied-de-Port both issued credencials from Les Amis du Chemin de Saint-Jacques (the friends of Saint James). In Spain, you can get a credential issued from the Cathedral of Santiago itself at the major albergues (usually municipal, but sometimes church- or volunteer-run) in the larger towns all along the Way. This turns out to be useful if you’re starting somewhere other than a “traditional” starting point, or if you’re a serious stamp-collector; the booklets can fill quickly! (I had an APOC credential that I filled walking from Le Puy to St Jean Pied-de-Port, and then a French credencial that carried me through to Finisterre).

In the end, my credential wasn’t just a way to prove to a guy behind a desk that I deserved a certificate written in Latin. It was a way to record each step of the journey. It truly was about the journey, not the destination. And when I got home, it wasn’t the Compostela I framed and hung on the wall; it was my two, wrinkled, faded, beautiful credentials.