Zenarruza to Guernica: 18 km; Guernica to Larrabetzu: 17 km

If I’m ever going to finish the stories of Camino del Norte, I need to start combining days. And actually, when I think about the end of our first week, these two shorter-distance Camino walks had a lot in common.

For thirty-five total kilometers, we were in the interior of Spain, one of the longest stretches of the whole trip that we were out of sight of the ocean. The countryside was hilly but dry, steadily ascending and descending through small Basque towns.

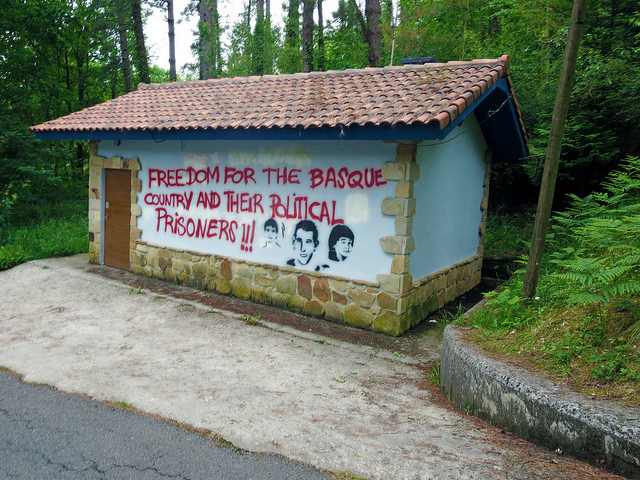

This was not Spain. This was Basque Country.

If we had any doubt, the sign welcoming us to Munitibar made it clear.

As did the graffiti (curiously, almost always in English).

We stopped for the night in Guernica (Gernika in Basque), a city made tragically famous for its political opposition to those in power. The history of it fascinated me. In 1937, the Spanish Civil War was stalled. The dictator Franco wanted to defeat the Republicans in northern Spain. He had the support of Adolf Hitler’s German Lutwaffe, but not enough strength on the ground to conquer his fellow citizens. Guernica had not been involved in the war to date, but it was the spiritual center of Basque culture and an important transportation point for reaching Bilbao. So on April 26, a market day when everyone was outside and the city was crowded with visitors, the Lutwaffe swept down and bombed, and then strafed, civilians. It was one of the first acts of “terror bombing,” deliberately targeting civilians and non-combatants from the air in order to break the will of the enemy.

No one can agree on how many innocent people died in Guernica that day, but the devastation of the historic center of the city was immense, as was the outpouring of outrage from around the world. Picasso’s famous painting Guernica (which I saw, coincidentally, in Madrid last year) tried to capture the horror and has been called “modern art’s most powerful statement.”

Today, Guernica is a thriving Basque center again. In fact, to be honest, I didn’t spend much time that afternoon exploring Guernica’s past. My feet were aching and swollen from the cumulative miles of the past week and the long walk to Zenarruza the day before, and so the best thing to do was rest, not try to tourist. Eric and I spent the afternoon in a sunny square with three pilgrim friends — Australian, Spanish, and French — sipping Crianza and watching kids play not far from the round market building that is one of the only structures left standing from that earlier time.

At least, that’s what I think the sign said.

Oh, the signs.

The primary language of the Basque people is Euskara, a language that as far as I can tell, exists to take advantage of all of the X’s ignored by the rest of Europe. Linguistically unrelated to any other language in the world, it flourishes in Basque Country, where 93% of all Basques use it. Children learn Euskara as their first language at home and pick up Spanish only when they go to school.

Which leads me to what happened in Larrebetzu.

We were enjoying a quiet afternoon in the small town on the outskirts of Bilbao, after another relatively easy walk. Eric and I had split up to find our own quiet corners to rest and journal. I landed on a bench in the center of the town square, which gradually filled with locals as they got out of work and school.

This is my favorite time of day in Spain, and perhaps my favorite thing about Spain in general. Every afternoon and evening, public spaces fill with families. Kids play and do homework. Adults sip drinks and gossip. Grandparents sit on benches and watch over it all. And here’s the crazy thing: no one plays with their phones. They are fully present and together.

Eric sat on the ground in another plaza, down a flight of steps and out of sight.

After a while, he noticed that a group of four small girls, all of them about five years old, was studying him curiously. They drew closer, and then closer again. He couldn’t understand what they were saying, but they were clearly talking about him.

Finally, the bravest one stepped forward and said, in English, “What are you doing?”

He looked up. “You speak English!”

They looked at him blankly. No, they didn’t speak English. They just happened to know one phrase. But now they were engaged.

The five of them spent the next hour patching together Spanish, as the girls tried to teach Eric Euskara words for whatever caught their attention, from balloons (globoak) to little brothers (anaia txiki). They took their responsibilities as tutors seriously. They corrected his pronunciation and quizzed him every few minutes to see what he remembered. This continued until their parents came to take them home.

Eric was exhausted from all the attention, but he still talks about that afternoon as one of his favorite memories. And we started being intentional about lingering in plazas and squares in the evenings, seeking the heart of each new place.